The Essential Importance of Learning The Money Game

You either learn to play the game or you get played

Over the last few days, yet another war has broken out in the Middle East.

This may be very sad and scary but it’s not at all surprising.

If this was a surprise to you, then watch this video from 2012. Did your boy here have a crystal ball?!?

The typical reaction of the rookie investor to war is to huddle in cash (a natural reaction driven by fear or anxiety).

Whilst this makes emotional sense, it makes no financial sense.

That’s because wars inevitably lead to higher commodity prices, more government spending and borrowing, more money printing and greater inflationary pressures. These things are all bad for cash savings.

Most people start their money journey by saving some money into a piggy bank or a bank account.

That’s better than buying consumer crap but it’s a long way short of what we need to do to grow wealth.

You either learn to play the money game or you get played.

Case in point: the cost of being sat in cash is not just measured by inflation.

Most people think that if prices are going up by 2% per year, the loss of purchasing power of cash under the mattress is 2% per year. That’s the cost of inflation.

This is incomplete at best.

The cost to the investor of being stuck in cash savings is better measured as ~8% per year (the rate of money printing) rather than ~2% per year (the rate of inflation).

Imagine a world where the government expands the money supply (the amount of base currency in existence) by 8% per year.

Imagine that it does this via a mix of printing new paper banknotes and also creating new money electronically at the click of a central bankers keyboard.

Now imagine no more because this is the world we actually live in!

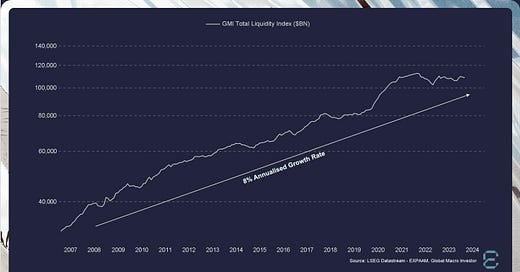

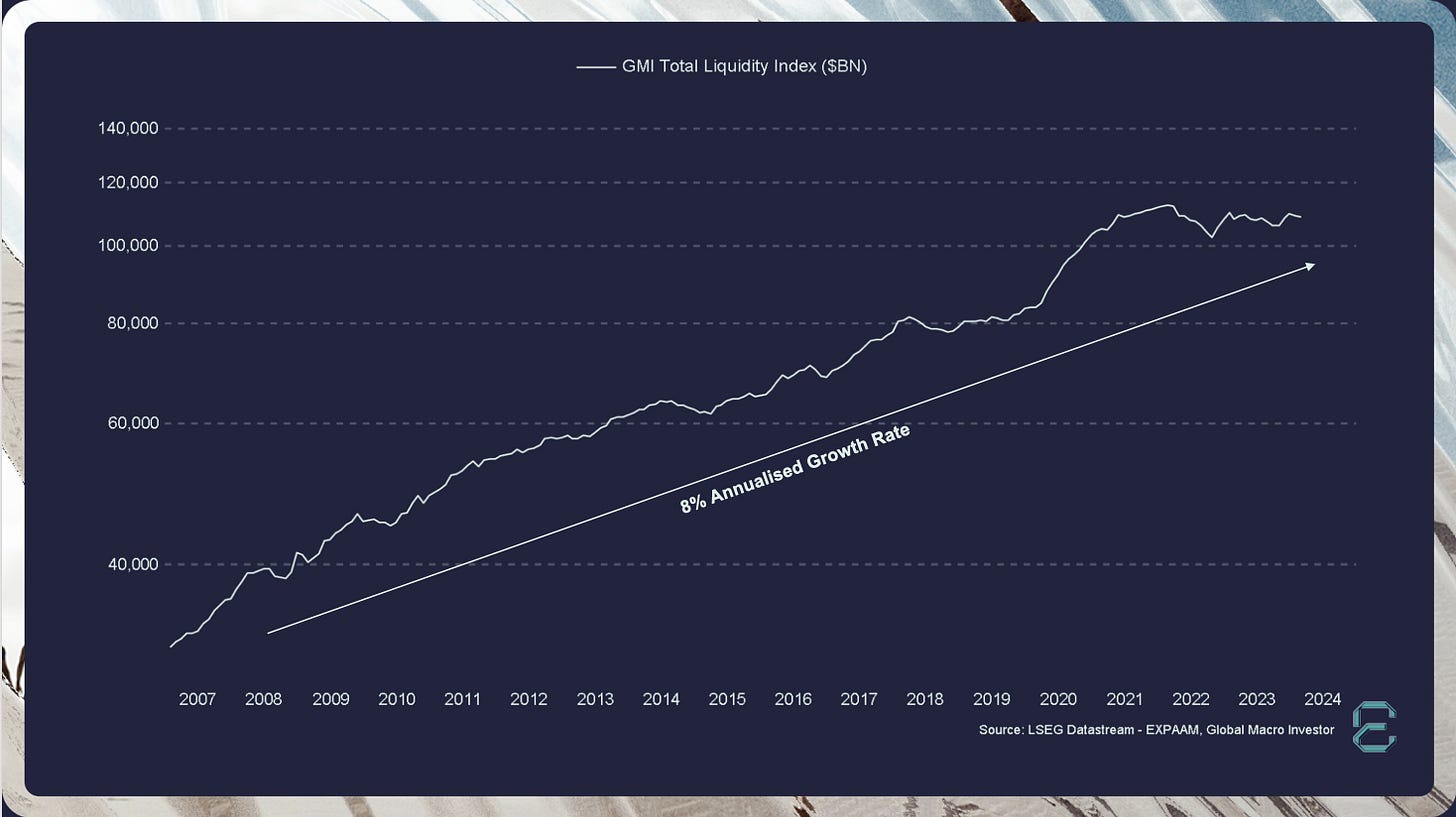

The chart below shows a measure of global money supply produced by Raoul Pal of GMI:

In the period since the global financial crisis of 2008/9, the rate of money printing has been approximately 8% per year.

At the same time, we know that the UK, USA, EU and other countries operate an inflation target of 2%.

What is the relationship between money-printing (which has averaged 8% per year) and inflation (which is running closer to 2% per year)?

Inflation has often been described as “too much money chasing too few goods”.

Milton Friedman famously said that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenum”.

In this model of the economy, money printing is the input (the cause of inflation) and the end result is rising prices in the shops.

All else being equal, the great the rate of new money creation, the greater than the inflation rate in an economy will be.

The UK government has set an inflation target of 2% per year. And let’s assume that inflation does indeed run in line with this 2% target.

It would be easy for the investor to measure the opportunity cost of sitting in cash as being 2% per year.

But the cost of holding cash is ~8% not ~2% because whilst we are sat in cash, hard assets (property, equities) are appreciating and running away from us.

To the extent that we want to buy these hard assets in the future, we are being left behind.

The rate at which this happens is about 8% per year. Global equities have delivered a 10% per annum return over the past 10 years.

If you take out the dividend yield at about 2% per year, that leaves roughly 8% per year of capital gains. Those capital gains represent the opportunity cost of being stuck in cash.

In a world without money-printing, inflation would be negative and the cost of living would be falling.

All else being equal, the great the rate of new money creation, the greater than the inflation rate in an economy will be.

The problem is that the economy is a complex system that is dynamic and ever-changing. So all else is never held equal.

In the period since the 1970s, the annual rate of inflation in the UK and USA has moderated due to factors including 1) globalisation and world trade 2) increasing automation 3) demographics.

It seems almost certain to me that, in the absence of Covid and the associated policy response (shutting down the economy and printing massive amounts of new money), inflation would have stayed down and hovering around the 2% per year target rate.

Source: Office For National Statistics

And, if we’d had a world with no money printing and no Covid, it is likely that prices in the shops would have been falling year over year.

It seems to me that if we were back in a world where technological progress was combined with hard money (e.g. the gold standard or a world without money printing), falling prices would be the norm.

The 6% differential between the ~8% annual rate of money printing and the ~2% observed rate of inflation represents the appropriation of technology / productivity gains by the government.

The better alternative to sitting in paper assets (cash or bonds) long term is to invest in hard assets (equities, property, gold) that can not be printed by the government.

Over time, money printing inflates the price of all hard assets (gold, property, equities).

Over the long term, cash is trash and bonds are a melting iceberg.

This is why its essential to set your asset allocation intentionally and take control of your workplace pension.

UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves has recently announced new proposed powers to influence / control workplace pensions. The government’s Pensions Investment Review Final Report contains full details of the proposed reforms.

The stated rationale is that this will allocate capital towards riskier investments in British businesses and infrastructure projects, with the stated aim of boosting UK economic growth.

If you trust the government to manage your pension investment decisions for you, then there’s nothing to see here.

Me? I do <not> trust this government (or others) to make investment decisions on my behalf.

The government proposals look like a form of soft-nationalisation of private sector workplace pensions. The government wants the power to force your workplace pension to become a vehicle for directing capital firstly towards UK plc (and then later perhaps to buying its own debt?).

This would allow the government to direct more capital to it’s favoured infrastructure projects and favoured private equity houses. The potential for either cock up (poor returns from incompetence) or conspiracy (poor returns from high fees, fraud and corruption) should be obvious.

If you are a coaching client or a subscriber to The Escape Manual, you can read more about this (and what to do about it) here.

Sorry, I don’t make The Rules. You either learn to play the money game or you get played.

Love to everyone

Barney

If you’d like to discuss financial coaching or career coaching, you can set up an introductory call with me here.

Please share this email with anyone you think could benefit…thank you!